Delta Voices: Justin Tyler Bryant

This summer, the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts launches Delta Voices: Artists of the Mid-South, a limited podcast and video series highlighting emerging artists working in the Mid-South.

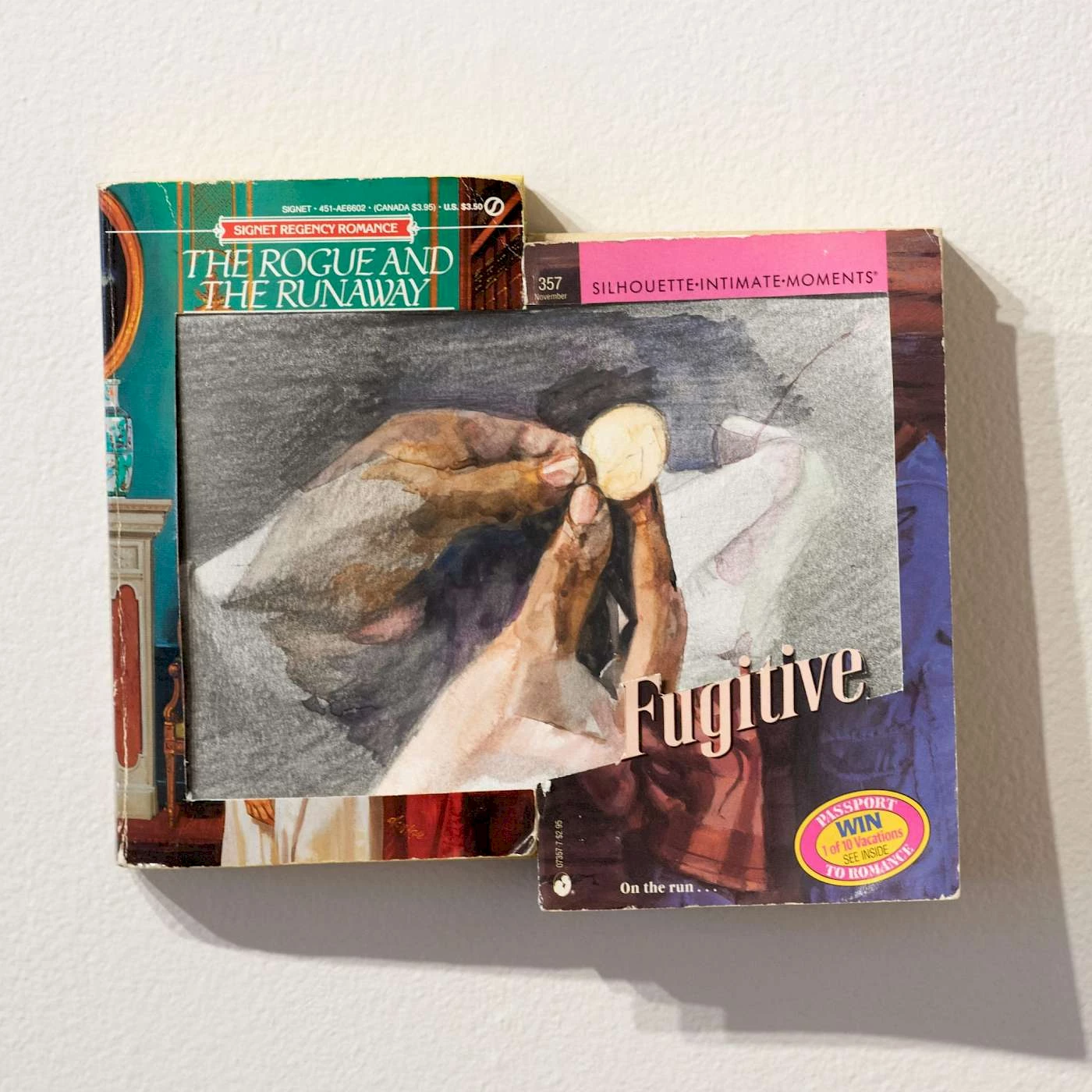

The series was created in collaboration with the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, and the Mississippi Museum of Art. Each of the four episodes features an artist selected by curators at participating institutions. The AMFA selected Little Rock artist Justin Bryant, who is known for his realistically rendered drawings and paintings of African Americans. Bryant’s most recent project, Holman: A Living Archive, documents a former high school attended by Black students during decades of segregated education in the artist’s hometown of Stuttgart, Arkansas.

AMFA associate curator Theresa Bembnister spoke to artist Justin Bryant in June. To hear more of their interview, check out the Delta Voices podcast episode on Spotify and watch the video introduction on YouTube. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Theresa Bembnister: What are the challenges of being an artist in the mid-South?

Justin Tyler Bryant: Hmmmm. Do you have time? I’ll start with the advantages. Because I’ve been here so long, I know more. I know who to go to for certain things. I was a student, then I left here and came back. I think I have a good perspective by being here longer.

The challenges—they’re the same for every artist, whether you’re in New York or California or Arkansas. You have the same challenges. It’s going to be a little different because you’re in the South, but with technology it’s not as bad. You can apply to things and know about things that in the past you couldn’t.

We don’t have a studio culture here. You’ve got to build a studio culture. That’s one of the things I’m always talking about with my friends. People need to know you can get a studio visit or invite people to your studio. To have really good art in a city, you have to have a good studio culture. That’s a main challenge, trying to create a community where people are making in the studio and inviting people in. With that said, we have so much space, so it’s affordable in that sense.

I think it has more advantages than disadvantages. The support here is really good. It’s a smaller community. Some people might hate that, and at times I think I do, but for the most part I’ve used that to my advantage.

TB: What keeps you here in Little Rock?

JTB: Family and friends.

TB: How does your family affect your practice? You often draw your family members.

JTB: They take my suggestions more easily. It’s easy to interact with them because I know them better. That’s always been the case. It’s just been easier to draw family because they’re there. It’s the same thing with self-portraits. You’re always available, so draw yourself. My family has always been available, so that’s why I draw them. When you draw a person’s face, you know them, because you are looking at the details really intensely. It’s a way of knowing people too, drawing portraits. When you sit there and draw them, they change a little bit as you’re drawing them.

It’s a different feeling when you know the person. Even in a figure drawing class, the best drawings come from when you actually know the model pretty well–when you’re familiar with them.

TB: You make a lot of drawings, but you also work in the area of social practice. Social practice, or socially engaged art, refers to an artwork that centers on community and often involves some form of participation. How were you introduced to the idea of social practice? Why did you decide to adopt that as one of your ways of working?

JTB: I think watercolor and graphite were leading me to dead ends. It didn’t matter how many times I rearranged an image, it didn’t quite do what I wanted it to do, which is make more of an impact. Now I’m looking at archives, my history and Black history.

I’m also interested in which artists were social practice artists without knowing they were, or they didn’t have a term for it yet. I think Augusta Savage had a social practice. If you think about the way she created the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, she gave kids an art education in Harlem. She stumbled into teaching. She got a scholarship to Paris and they took it away because she was a Black artist. She wanted to make art, but she ended up doing more community-based things. That’s social practice. Some of the artists she taught became really well known, like Jacob Lawrence, who was a kid in her art classes. As Black artists, it changes it a little bit because that was the only way they could make a living. They can’t sell their work. That’s already a problem anyway for any artist, but in particular for Black artists that was really the only avenue at that time.

TB: How does your role as an educator affect your practice?

JTB: I teach at the University of Arkansas-Pulaski Tech in the drawing department. I think it affects my practice because I think about it every day. Every time I go into a classroom explaining something to a student, I’m always changing how I describe it. And the students always ask great questions and make me change my mind.

Check out Bryant’s online portfolio for more of his works, and follow him on social media @bluedrinknotredb